Introduction

Introduction

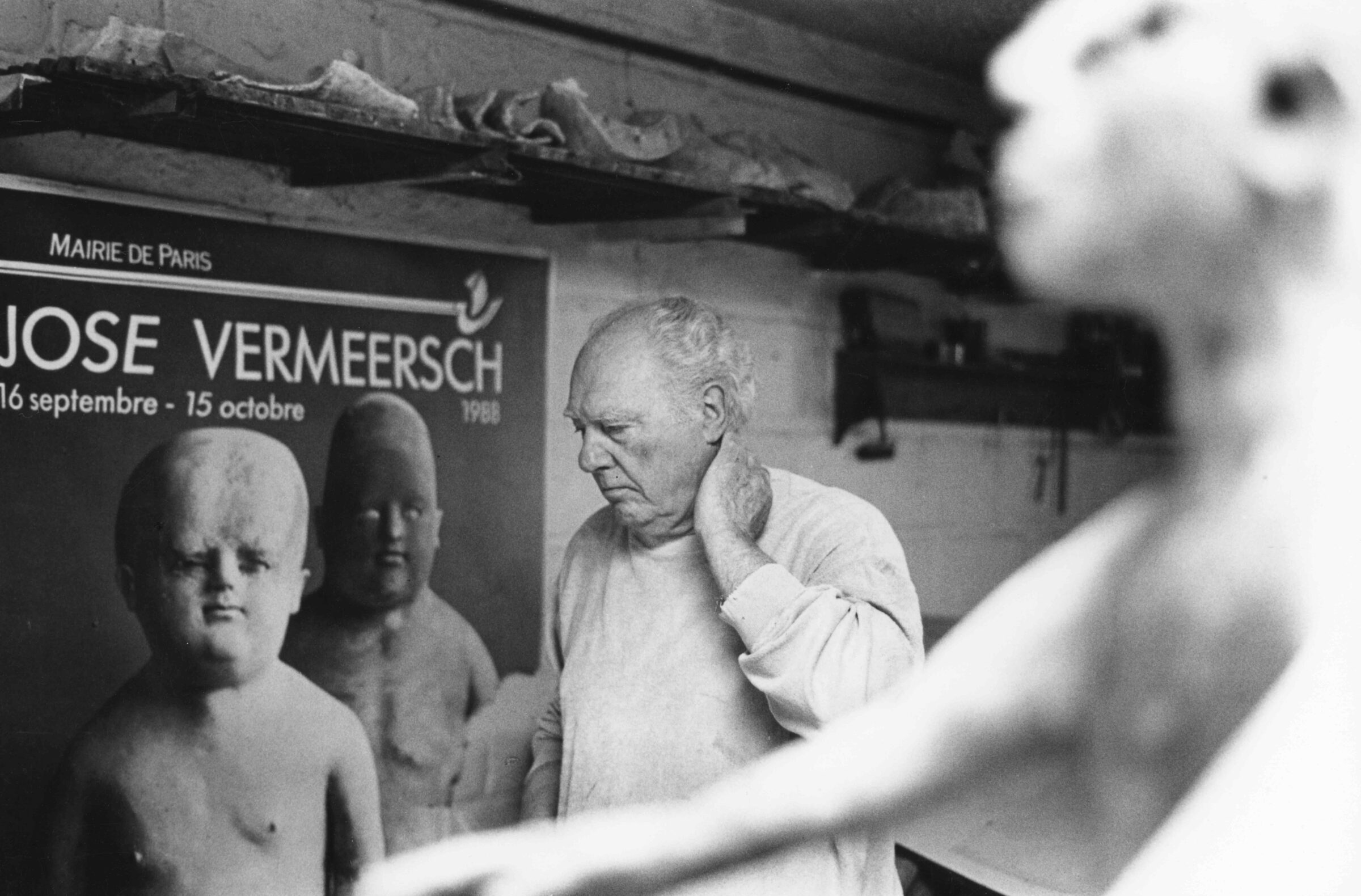

The Belgian sculptor José Vermeersch (Bissegem 1922 — Lendelede 1997) is a loner in post-war sculpture. One will therefore look in vain for him in art history handbooks where everything is carefully ordered in movements and isms. In his sculpture extremes meet, from the terracotta figures from the tombs of the Ch’in dynasty to the American pop art of artists such as Duane Hanson, George Segal and Edward Kienholz. Vermeersch, a student of Constant Permeke and Walter Vaes, began as a painter. In 1969 he permanently switched to working in ceramics, later also in bronze. His almost life-size sculptures — people and dogs — are built up from thin sheets of clay, which makes high technical skills. The human figures, outwardly impassive but with a great expression, are alone with themselves; the dogs are there as their faithful companions.

José Vermeersch was born on 6 November 1922 in Bissegem, near Kortrijk. From as early as primary school age, he was already showing great skill at drawing and painting. In 1937, he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Kortrijk. Although fascinated by all genres, it rapidly became clear that his great talent lay as a portraitist. He has the effortless knack of rendering a countenance, of capturing an authentic expression. His realism is academic without being cold. As a good observer, he has an eye for detail. In his compositions, he makes it his task to chronicle the daily life of ordinary people. He describes their-day-to-day existence, making no social barbs or comments, without indulgence, and yet with a hint of romanticism.

In 1941 he enrols at the Antwerp Academy, valuing the teachings of Walter Vaes more highly than those of Isidoor Opsomer whom he accuses of excessive technical virtuosity. In 1943 he is obliged to interrupt his studies. He goes underground in order to avoid being shipped off to the forced labour duty in Germany. He seeks refuge in Westvleteren, not far from Veurne and the French border. During his enforced retirement, he produces an eclectic set of works. He is clearly in search of a personal theme and style, but has not yet found them. Some of his works strike us with their freshness of expression, conjuring up animism. But he also allows himself to be drawn toward expressionism in the style of Permeke. However, his portraits always remain true to an academic realism. As soon as hostilities are ended, he resumes his studies at the Antwerp Academy under a new generation of professors, including Constant Permeke and Roger Avermaete.

From 1945 to 1958, José Vermeersch searches relentlessly for a personal orientation that he might give to his art. He realises that he could be able to make a living of sorts by painting portraits – a discipline in which he excels – but it is not enough to satisfy the aspirations of the young artist. He thus embraces a monumental art, related to muralism and the pittura metafysica of Chirico. Abstract painting leaves him cold and surrealism is the in thing. From the end of the 1940s, he abandons this particular direction.While continuing to turn out portraits to order in a purely academic style, he endeavours to simplify the representation. He is fascinated by the quest for the essential.

In other words, the primary goal is to render the sitter’s expression. How far can he go in this quest for simplification? One technique he uses is to accentuate the geometry of the physiognomy, leaving out detail, skipping finishing touches.

As for his landscapes, one can’t help mentioning a strange work that clashes with the rest of his production at this time. The subject is a fairly banal one: a perspective view of a road with a surface made of concrete plates. Vermeersch holds back his use of colour so sternly that the work brushes up against minimalism. But do not be deceived, for there is a great deal more in the work than first meets the eye: plays of light and shade, careful rendition of the asphalt, interplay of clouds. The work inaugurates a new period of research. Easel painting no longer satisfies him. He considers that in the modern world, painting must be integrated into architecture, whose dominating role he recognises. This is an idea he attempts to express in a whole series of works. We note the purged architectural volumes used to lend rhythm to the composition. Structured in this way, the tableau takes on constructivist allures, immediately contradicted by the elaborate treatment of certain details.

Toward the end of the 1950s, it appears that Vermeersch has not yet discovered a mode of expression corresponding to his temperament. His quests lead him in a multitude of different directions, sometimes frankly contradictory. This is proved by the fact that very few of his works from this period are with us today. It is probable that we lack a certain number of key works in order properly to document his evolution.

The interest shown by José Vermeersch in architecture goes hand in hand with an increasing aversion for easel painting. In his eyes, the brush and canvas are old-fashioned means of expression for which an eminently modern alternative needs imperatively to be found. For this reason, he exhibits a series of ceramic panels in 1959. The step clearly shows his wish to integrate with architecture, while it cannot for a moment be said that he has managed to shrug off his constraint of painting. Very soon he grows weary of the decorative side of these works.

He imagines he has found a valuable alternative in a self-invented tracing technique and will practise it for several years to come. Vermeersch proceeds as follows: he cuts out a tracing template in cardboard according to the exterior contours of the subject of the piece. This template is covered with paint, applied to the canvas, and then pulled off again sharply. The operation is repeated until the desired result is achieved. A few finishing touches with pastels, charcoal, or crayons are sometimes added to complete the tableau. Diametrically opposed to the stencilling technique, this procedure allows interesting textural effects to be achieved. The cutting out of the template has stylistic cues: the forms and attitudes are stylised and depersonalised. Here in any case is an oeuvre that is easily identifiable, corresponding to Vermeersch’s taste for the monumental. His themes bow to the demands of his method. They take their turn in a universal, anti-anecdotal manner: sitters in poses of varyingly hieratic degrees, parents and children, domestic animals.

Early Years

Early Years

Vermeersch becomes quite taken with it and attempts to prove that his tracing method is not an impediment to treating subjects requiring a more meticulous approach. In this spirit he produces a range of surrealist works in which he delights in rendering an infinity of detail with the dedication of a miniaturist. Sometime around 1965, a new direction emerges. Vermeersch returns to the brush, but his style has evolved dramatically. No more details and finishing touches: on the contrary, the execution is composed of large sweeps and grand flourishes. These are the tangible signs that technical mastery and thematic maturity have finally been acquired.

Throughout his career, José Vermeersch is interested in sculpture. With no particular apparent preference for this or that material he carries out a number of experiments in the field in the 1950s. At the start of the 1960s, he gradually discovers the possibilities offered by ceramics. He produces a number of well-executed torsos and animals characterised by a simplicity and purity of line. He is by no means immune to the charms of potter’s clay, mixing and matching it into a variety of different tones. This material with its fine, ductile texture, with its infinite marbling, offers him perspectives only glimpsed until this moment.

The end of the 1960s represents a radical evolution in José Vermeersch’s painting. He finally rids himself of any aesthetic preoccupation, of suffocating idealist pretensions. In a fluent, libertarian style, he paints a view of humanity reduced to its simplest expression. Each canvas represents an ever more asexual sitter, devoid of contingencies and constraints. This evolution is stepwise in nature, but these steps take place at an accelerated rhythm between 1966 and 1968. At the start the sitter, placed in a non-specific environment, finds himself or herself incongruously confronted with a clearly identifiable and strong object, being a box, apparently empty. This object, whose single finality is to exist but for the grace of that which it is imagined to contain, appears to Vermeersch to be the ultimate reminder, oh how banal, of society and his efforts to remove himself from it. In later works, the physiognomy and anatomy further separate. Physical points of reference — sun and horizon — fade away, then disappear completely. This painting ends up by concentrating on the silhouette that accentuates a virtual halo.

These sitters, vaguely male, vaguely female, represent a new humanity, one which is a noticeably long way away from the humanity he advocated at the start of his career. The New Man is eminently free, devoid of contingencies, even his sexual adherence. He is supremely indifferent to his surroundings.The following stage is foreseeable and even underway. The sitter will be detached from the canvas, removed from a two-dimensional world.

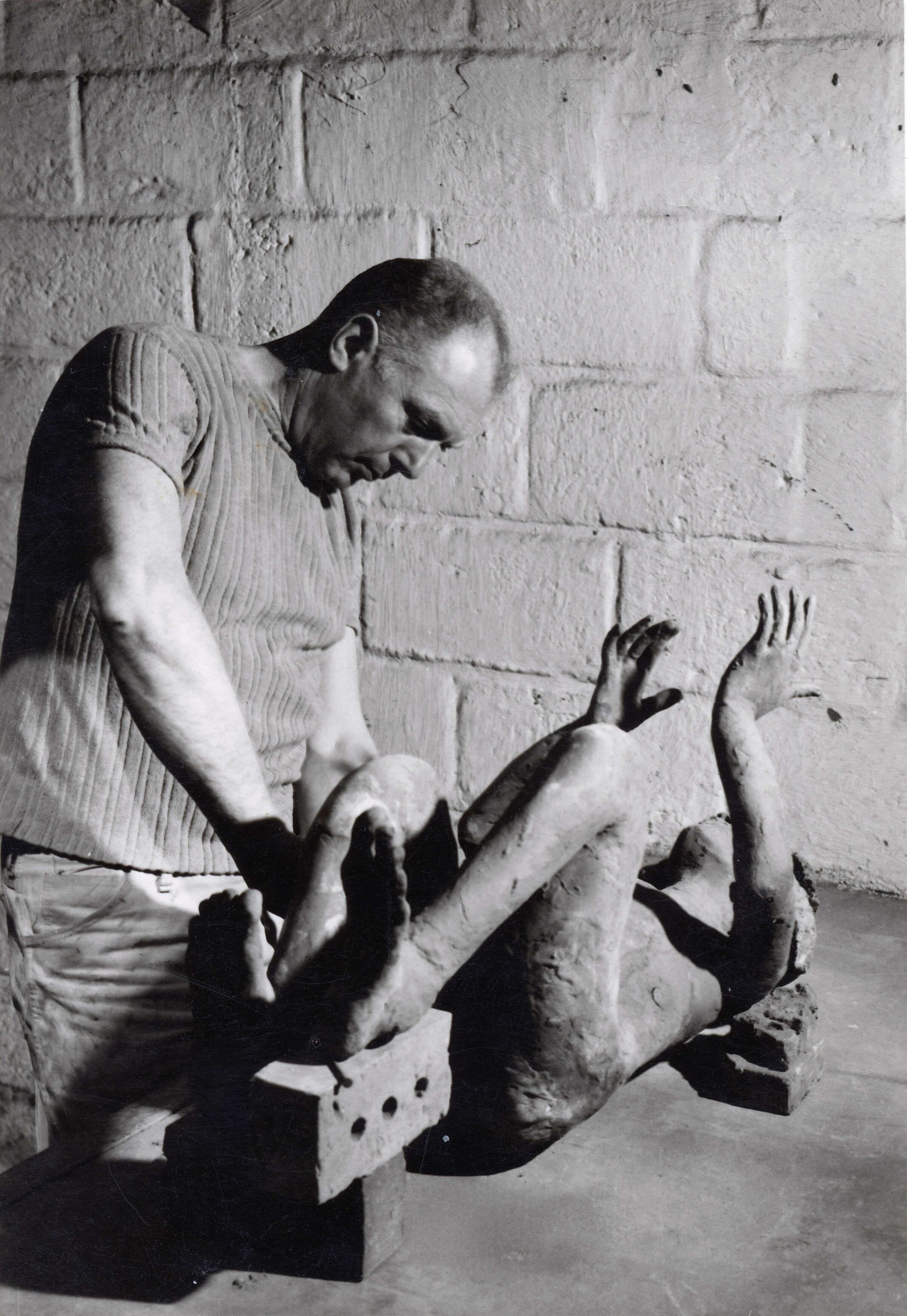

Around 1969, two-dimensional expression is no longer satisfying José Vermeersch. He turns back to ceramics. In comparison with his experiments at the start of the 1960s, he now possesses two major advantages: a visual programme borrowed from his painted oeuvre, as well as an innovative method of hollow ceramics. Instead of working in solidity, Vermeersch constructs his statues by placing clay plates, which he has beforehand processed, amalgamated, and formed into astonishingly thin leaves. First he fashions the feet, then the legs, then the torso, and finally the head, observing moments of rest to allow his material to dry and harden. This method is thus of capital influence in the aura of the statue. Standing on its own two feet, it is well supported on solid legs. The subjects are presented to us in unstudied attitudes, marking their astonishment in front of very existence itself. The torsos, though often voluminous, never give an impression of heaviness. At no time are we allowed to forget that they are hollow, that these carcasses are merely floating in the air they occupy. Freed from the constraints of canvas, the subjects take possession of their own space, so Vermeersch represents them in extreme, not to say exuberant, poses. This excess does not detract from the quality of the expression, although this gestuality rapidly evolves toward a greater reserve.

But at the start, all is undiscovered. So Vermeersch studies the impact of the use of colours: engobe white, flesh pink or ultramarine blue, painted plays of light and shade. Accessories, audacious or otherwise, make their appearance: real hair, necklaces and pendants, sometimes even a pair of spectacles or a dog’s leash. For at the side of man, the dog makes his appearance. Vermeersch’s canines are of the mutt variety. The product of anything but selective breeding, they are stocky and robust, and what they lack in elegance they also lack in inhibition.

Vermeersch increasingly sees the possibilities of his work. He appreciates the added value of grouping his statues. “De Kennel” from 1973–1974, a work selected for the (aborted) Venice Biennial, consists of nine humans and five dogs. The juxtaposition of these introverted specimens of mankind is outrageously gripping and illustrates the deep contradiction between the amorphous nature of the characters and their membership of a group. The reserve, or even indifference, of the humans is in flagrant contrast to the attitude of the dogs with their somehow association to the children. They all dive into the game and the effrontery.

Colours, accessories, and tricks become superfluous. The subject material is sufficient in itself. The statue expresses everything. Vermeersch is fascinated by the tones of the clay he mixes. He exploits the marbling that appears in a less than perfectly amalgamated mix. He goes further, intersecting blocks made up of dark and light layers. He even goes so far as to copy regular designs with squares, dots, grooves, you name it. Thus he mischievously suggests the edgiest hint of clothing. But these structures are also to be found with no reference of any discernible type in his nudes, his torsos, in forms both sophisticated and rustic.

José Vermeersch’s ceramics immediately undergo a considerable frisson. Thirty years of painting in an air of studied indifference have blossomed into an acutely original mode of expression that is lapped up virtually without reserve by the public and the critics alike. This popular success and the new perspectives offered to him by ceramics propel him into a giddy new whirlwind. Exhibition after exhibition follows, sometimes colliding, always at an ever greater rhythm. Orders flood in, and yet he never loses his taste for exploiting new creative formulas. The upshot is a substantial production, a production indeed worthy of his own substantial constitution.

Build Up

Build Up

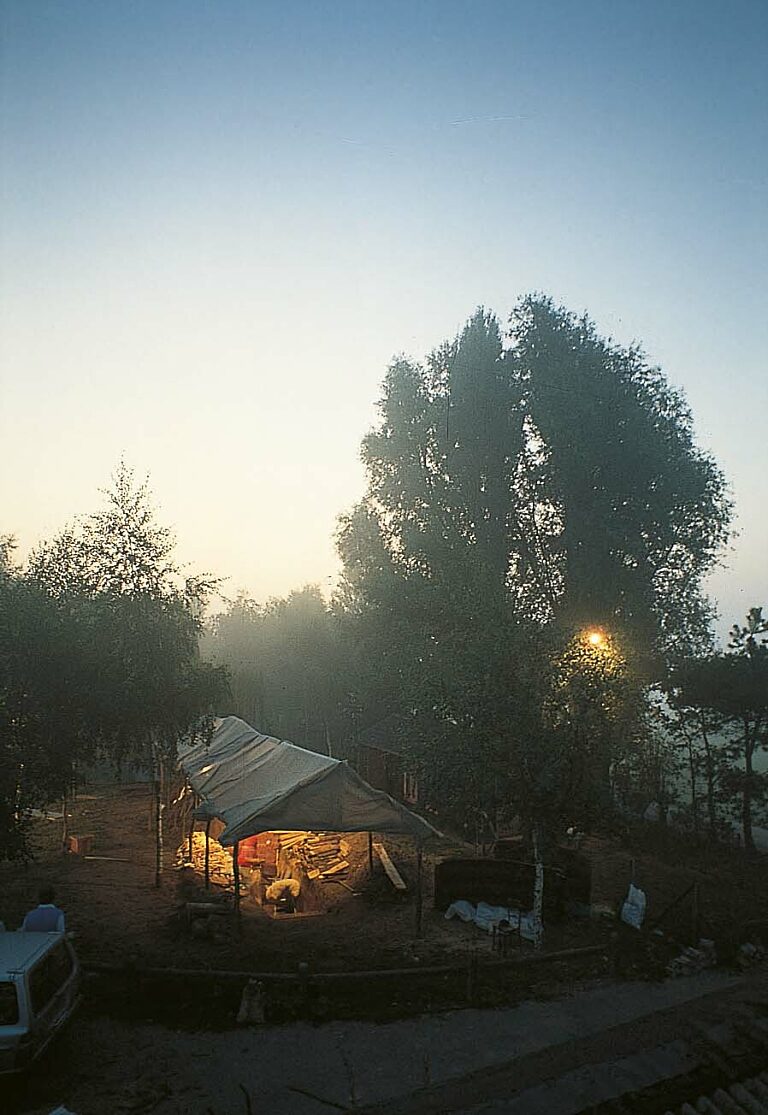

In 1979 Vermeersch renews his links with handicraft traditions. Driven by the taste for a challenge, he designs a traditional wood-fired kiln and then with the help of a number of friends actually builds it in the middle of the countryside. This delicate and demanding operation takes place in an atmosphere of festivity and conviviality. It is a hands-down success. For Vermeersch this experience marks the peak of ten years of ceramic creation. However, the 1980s start off in a climate of crisis. Although the public is none the wiser, Vermeersch fears that he has exploited all the creative possibilities of ceramics. The nightmare of repetitive work, without the adrenaline of innovation, torments him. Thus he is driven to find renewal of his themes and technique by any available means. When directing a seminar for young ceramics artists in the Dutch town of Heusden, he turns his hand to the delicate work of porcelain. The result — essentially decorative in nature — is a production of minuscule statuettes, some of which he arranges together to form veritable little scenes of narrative.

An abrupt change of heart follows in the shape of an appealing series of torsos. Once again, he shows off his perfect technical mastery, both in the texture of the material and in the lifelike naturalness of his work. Finally he surmounts the crisis when he organises an exhibition on the theme of “Conversation”. His characters, arranged either in couples or in larger groups, include an orator with a number of eager listeners. This adjacency of characters is thus enriched by a totally new dimension, that of communication.

A communicator too, but a communicator of a different sort, Man’s Best Friend takes up a more assertive role than in the past. Vermeersch accentuates the canine’s anarchic character. Dogs and children are not in the least bit interested in the games adults play. They draw their vitality from the game and by mocking everything that is serious and respectable. Vermeersch’s reputation is now beginning to cross borders. His participation in the 41st Venice Biennial in 1984 is noted far and wide, and consolidates his reputation abroad. In a period stretching less than a decade, he is the subject of several major exhibitions in the Netherlands, Mexico, France, Germany, and the United States.

Perhaps it is now the moment to mention something crucial: Vermeersch starts painting again. Though when starting his ceramics production he had hoped to mount a two-front assault with his activities as both painter and ceramic artist, he was soon forced to submit to the evidence that it was all but impossible to stick to such a course of action. Between 1971 and 1982 he hardly painted at all. The result was that his painting and his sculpture evolved in different directions. His canvases of the 1980s are executed in a meticulously realistic style which owe more than a little to the hyper-realism that was so fashionable at the time. His portraits too observe the same aesthetic. Whether a landscape, a portrait, or a still life, his overriding quality is one of luminosity. For him, you see, there is not a single stylistic distinction between these renowned genres. They may be very distinct from each other, but there is no distinction between them.

Closing Years

Closing Years

In the closing years of his life, the work of José Vermeersch is characterised by the mark of continuity, while never being divorced from the emancipation of technical experimentation. He stays ever faithful to his cast of characters; an archetype of new-born humanity, with neither knowledge nor experience, a shocking initial contrast to the discovery of his own existence. The beautiful china shop is upset not by bulls, but by dogs. Rebellious and facetious, they gladly feign the strange behaviour of humans, mocking their so-called superiority.

Vermeersch now makes a substantial number of sketches. Some of these are designs for monumental statues that he is planning to produce in bronze. In contrast to the bronzes turned out from his ceramic work, this new sculpture takes a different spirit as its starting point. Though his cast of characters retain their physical features, they no longer express that ephemeral state of primary innocence. Their solidity underscores their permanence. I’m here, they say, and I’m here to stay. And nobody’s ever going to get the better of me.

In the same way that he plunged into porcelain, Vermeersch now plunges into techniques that are new to him, with the heartfelt hope of opening new perspectives in his work. He creates a series of figurines in blown glass. Sadly, the venture is less than overwhelming. Nevertheless, the characteristic raku crackling suits his tadpole characters perfectly, both accentuating the curves of their bodies and revealing the finesse of their atrophied limbs.

Painting lends him ever more satisfaction. In it he sees the perfect escape from his successful ceramic work that binds him to a relentless commercial rhythm. He goes back to his roots in portrait painting. The goal is the same: rendering the essential. And he does it so: facing his subject square on, abandoning the background, abandoning pretty details, abandoning any divergence that might draw the attention away from the sitter. A curious series of twin portraits done in gouache lets him evaluate the distance between the portrait and the après nature and his simplified interpretation.

Vermeersch’s last works are breathtaking sea views painted with an incredible brio and marvellous sweeps of richly contrasting colours. In the drama of his work, he expresses the fascination he has for the North Sea. Its unique and changing luminosity deservedly earns him a place alongside his beloved teachers and Grand Masters: Permeke, Ensor, and Spilliaert. A brief illness claimed José Vermeersch on 13 December 1997 in Lendelede. He had just celebrated his 75th birthday. — Rik Sauwen